Helpful Hints

A collection of tips and tricks to help you with your entries.

The Fear of Moving Past Blocking

By: Eric Scheur

Published May 18th, 2009

Back when I was in school, my classmates and I clambered about for any online information about animation we could find. This was just at the beginning of the era when blogs were getting to be popular, so in addition to the community sites and tutorials that had been around for years, many professional animators were starting their own blogs. Some posted sketches, some reported on the wacky antics of their co-workers, and others linked to music videos, short films, and commercials whose work they found inspiring.

Jason Schleifer, already a household (okay, animator's household) name from his work on the Lord of the Rings trilogy, had his own blog to chronicle the progress of his short film and fill readers in on the details of his life.

Jason also occasionally posted some of his thoughts on animation. I can clearly remember the day I tuned into his blog and read a post that would significantly alter the way I approached animation from that day forward. Many of my friends and colleagues were equally influenced by this simple but powerful idea and it quickly made its way into their workflows as well. Not only did it change the way I worked, but it opened my eyes to a new way of approaching any project at all.

Today, with Jason's permission, I am proud to re-publish his influential words here at the 11 Second Club. Ladies and gentlemen, I give you....

The Fear of Moving Past Blocking

By: Jason Schleifer

Originally Published November 16th, 2005

The more you know, the more fear you have.

Seems to be a rule true of many things; tree climbing, for example. Before you know about gravity and how much breaking an arm can hurt, you really don’t worry that much about falling out of the tree, you just sorta climb on up there and monkey around. It isn’t until you see your friend slip and fall and break her arm when you think “ohh... wait... this can be painful…” and you start to worry.

The same is true about animation.

When many animators first start animating they just move things around willy nilly, making things go this way, that way, etc. They have no fears, they just move things.

Granted, their animations may look like ass squished up against a large pile of roadkill, but at least they have no fear.

Once an animator learns about the various stages that professional animators use to work through their shots (e.g. blocking, first pass, second pass, and polishing), that’s when fear starts to set in.

It’s a pretty frightening prospect to spend a lot of time getting a blocked animation to look right--to make it feel perfect, get the timing all snappy, the poses to sing, and the intention to come across--and then convert everything to spline and suddenly it feels like total poop.

So many animators have a really hard time making the transition from clean blocking to clean first pass animation. It’s easy to become overwhelmed and just start throwing keys in randomly to try and make things look good, but they have no plan, no process. They know the stages, but they don’t know how to use the stages to their best advantage.

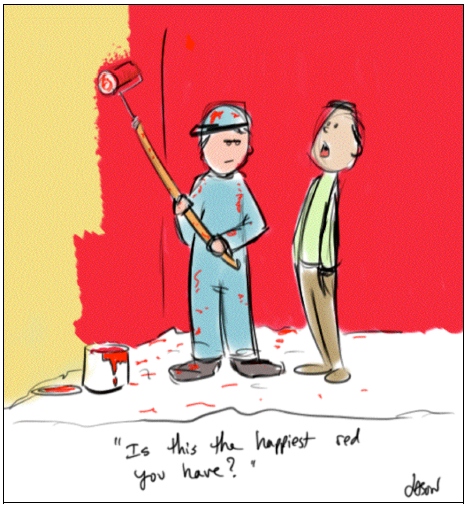

What I like to do is think about animating like painting a room. You want to be creative, but it’s important to be creative within the confines of what the client wants and give them the right information at the right time.

For example, if the client says they want a warm room with an accent wall that really brings out some dramatic intensity, a painter wouldn’t run to the room, grab a few buckets of paint, and start mixing them on the wall right away to try and get the right look. If they did that, they wouldn’t be able to guarantee the right color, the right walls that the colors would be on, they’d get paint all over the fixtures in the room, and the client might be pissed off.

No, they’d block things out first. They’d find the right colors for the walls and show color swatches to the client in the environment they’re looking at. Then, once the colors were approved, they’d tape off the fixtures and floors so they don’t have to worry about getting paint on them. Then they’d prep the walls, then paint one coat, then a second coat, then remove all the taping.

They would work in stages, so at the stage they’re currently at.--say painting the first coat of paint--they’re not worrying about things they should have focused on earlier (e.g. whether or not the paint is the right color, or if they’re getting paint on the floor, or if the walls were prepped). They work systematically.

Animation works the same way.

When we block our shots, what we’re doing is telling the director "This is my intention. I want the character to be here, thinking this idea, at around this time. Then they’re going to be over here.” Some shots require more blocking and explanation than others, but in the end, the whole idea is to let the director know what’s in your head and make sure that what’s in your head matches what’s in the director’s head.

When you move from blocking to the first pass of animation, this is where a real systematic approach comes in handy. It’s what allows you to animate quickly and with consistent results that will help the director trust you.

What I like to do is first break my shot up into distinct beats. This doesn’t mean that the shot will stay in this pose-to-pose style. What it means is that I’m simply breaking my shot down into easily discernable chunks. All I want to do at this point is move from a step-curved blocking method to a clean, easy-to-read first pass. So my shot is of a character sitting who then reaches over to pick up a glass and takes a drink. I’d break up the shot into three sections. Maybe frames 1 to 20 are of the character sitting. Frames 21 to 28 are of him reaching forward to get the glass. 29 to 35 are the character bringing the glass back up to his lips, and 36-45 are the character taking a sip. In the final animation, a lot of this motion will be blended together to feel like one solid action, but at this point my desire is to make these general sections feel right. I want the change in direction to work, and the arcs to work, and I don’t want to be distracted by trying to animate the whole shot the whole time.

So I’ll shorten my timeline from 1 to 45, down to 1 to 20. Then I’ll look at what’s driving the motion. Usually this will be the torso, so my first step is to clean up the torso’s motion and make sure it’s nice and clean.

I hide the arms and legs. I know that in the end I’ll need them to work correctly, but because what the body is doing affects them, it’s really easy to become distracted by their motion when I really should just be focusing on what the body itself is doing and making that clean.

Then I’ll convert the body curves to “clamped” or “spline”--whatever I feel is going to work best for this motion. I’ll analyze what it is I want the body to do and make notes before starting to move keys around. This way I have a plan. Then I’ll go through curve by curve, adjusting them as necessary to get the feel of the body moving forward to work correctly just for the lean forward. I can’t stress this enough. While I know the whole animation consists of a lot more than just moving forward, that’s all I’m focusing on at the moment.

I’m breaking down the motion into easily digestible chunks.

Once the body is working correctly for that section, then I’ll show the arm which is reaching forward and work with the animation of just that arm for those first 20 frames.

Now this may or may not be the final animation that I’ll be keeping. All I’m doing is making sure that this section is clean and easy to work with.

Next I will move on to the next section of animation, say frames 21 through 28 when the character leans back with the glass. So I’d change my frame range to start at 20 and end at 28. Then, again, I’d hide the arms and legs and just get the body moving correctly. Then I’d show that main arm and get that working correctly just for the section.

Once those sections are working, I’ll move onto the next one and continue until I have the animation clean for each individual section. Then I’ll playblast the entire thing and watch the whole animation, making notes of what changes I’ll need to make for the transitions between sections to clean them up. Maybe it involves delaying the arm, or adding more overlap into the body, or changing a pose, or adding or removing some time, etc. But at this point it’s easy to make these changes because we’ve gone about the whole thing systematically.

So if you can learn a technique like this, or come up with something that works for you, you can start to reduce the fear of going from blocking to first pass animation and begin thinking more about acting and the art of animating, instead of sweating the technical details.

Thanks again to Jason for allowing me to re-post his work here at the 11 Second Club. I sincerely hope it will inspire as many people as it did the first time it appeared on his blog.

Until next time, my friends, happy blocking and beyond!

- Eric

comments powered by Disqus